For the last 12 months I have been publishing regular articles on racial inequities in the arts with the aim of driving more open conversations about racial bias, its causes and practical solutions. While engagement with the articles is high, there is hesitancy among all demographics when it comes to sharing opinions publicly. More than 50% of responses I receive have come via direct messages rather than publicly shared comments.

When asked, people gave a variety of reasons for choosing not to share their views publicly. These include issues of privacy, employer constraints (such as working for a public broadcaster), not wishing to appear ill-informed and a belief that as a white leader you should leave the conversation about solutions to racial equity to people with ‘lived experience’. Each of these reasons – and there are more – would merit an article on its own. In this piece, I focus on what I think is the biggest barrier to participation: political correctness.

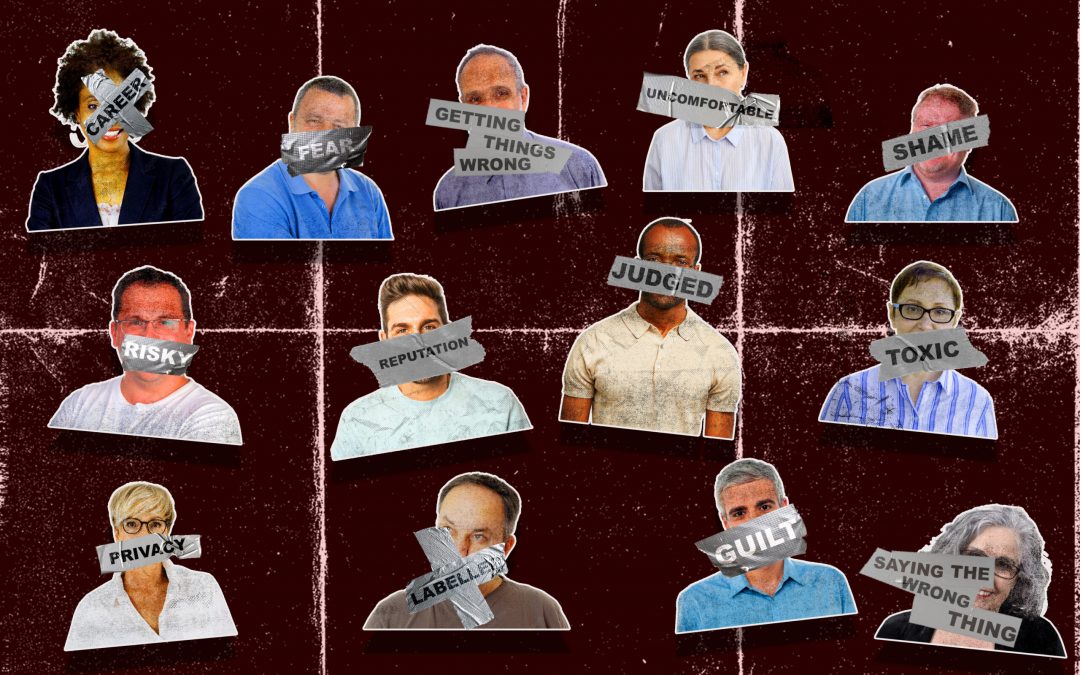

The readers of my articles – who include senior leaders, managers and administrators in the arts – often have strong, interesting and important perspectives. However, when asked, people from all communities say they are uncomfortable sharing their opinions because they are fearful of saying the wrong thing and being judged.

Fear of saying the wrong thing

Conversations on race generate emotion. They can ‘trigger’ people and opinions can be received with judgement. They can become a minefield of political correctness. When sharing views on the extent of racism, its causes and how it might be solved, you risk causing deep offence if your opinions are deemed to be insufficient (not radical enough) or inappropriate. Online, this can lead to personal attacks which can quickly be amplified, ending in condemnation and a risk to professional reputation.

The term ‘racist’ is one of the most unacceptable labels in our society. No one will publicly admit to being racist; not even supporters of far-right political parties, much less more left-leaning communities in the arts. Any potential accusation sparks fear to the heart, making open debate more difficult.

The severe and multiple impacts of racial injustice make negative reactions natural. But if our goal is to end racism, we must question the extent to which public shaming helps us – or not. Racial prejudice can’t be ended without forensic diagnosis of the problem. To achieve this, open conversations are critical. The more people engage, the better our collective understanding of the problem and the more effective the solutions become.

There absolutely needs to be room for challenge, but challenge that is constructive. This is harder to do when tensions are high. To take some heat out of these conversations and shed more light on the extent of racism, it’s important to find a new and more socially acceptable definition of the term ‘racist’. One that people don’t necessarily feel proud of but can at least ascribe to, with regret but not shame.

De-weaponising the word ‘racist’

Ibram X Kendi’s work on anti-racism helps with this. He contends that there’s no neutral position on racism: if you are not pro-actively ‘anti-racist’ then you are racist. He defines racism as any idea which suggests that Black communities are responsible for the systemic disadvantages we experience. What’s interesting is that, for Kendi, although holding such views is highly problematic it is not sufficient cause for writing someone off.

He understands that this thinking is itself a product of systemic racism and that we are all subject to it. Black, white, left wing or right wing. Racism in his world has no colour or political affiliation. He freely admits to having held racist opinions himself and says the same of some of his heroes like Frederick Douglass and Barack Obama. So, for him, racism should not be used pejoratively, but simply as a descriptor of a way of thinking.

In conversations about race, the reaction to anything deemed ill-informed or politically incorrect is often criticism in which racial prejudice is either inferred or implied. Any accusation or suspicion of racism is toxic so many prefer to remain silent or express their views in a safe space rather than running the gauntlet of sharing their opinions publicly. Kendi’s widening of the definition makes racism more ubiquitous so it’s harder to judge others as most of us are likely to have been guilty of racism at some point in our lives.

Power and responsibility still matter

None of this lets the predominantly white leadership of our sector off the hook. In fact, it may create the space to better hold them to account. While in Kendi’s view we are all likely to be guilty of racist thinking, ultimately it is still those in power that have most responsibility to change things. Using his approach, we can de-weaponise the word ‘racist’ and reduce its emotional impact in conversations.

With a less polarising definition we are free to name racism where we see it without the shame and possible consequences that come with it. We can avoid the emotion that prevents us from fully focusing on the job in hand, gain a better understanding of this pernicious problem and move towards the implementation of solutions.

This won’t be easy: it will require patience by some, bravery by others and goodwill by all. We are all gatekeepers in these conversations. Let’s begin, one conversation at a time, starting here!

We are keen to keep the conversation going. To read more and share your thoughts on this or other articles, connect with me on LinkedIn.