I have combined my two latest articles into one place because I think the first gives important context for the second – but for those short of time the articles can be read independently of each other.

My journey from shame to activism

Growing up, my instinct as a black child was to belong. If I (a foreigner) was compliant, then perhaps they (the white community) would accept me. As such activism was an anathema.

Being an outsider meant having no right to social or political dissension. I would have been ashamed to be called an activist, and I was embarrassed by those in my community who dared raise their voice for racial equity.

Prejudice as a natural instinct

Like many children, I internalised racism. This happens because children categorise others based on distinguishable physical characteristics, like colour and gender. The tendency is natural, but quickly turns to racial or gender prejudice if left unchecked. Children as young as three associate race with traits like intelligence, honesty and attractiveness.

As children adopt stereotypes, they start to use them to understand established social hierarchies in society. They then position themselves within them, according to their own physical characteristics – as someone who is black, white, female, male, black female, white female, and so on. I wanted to belong to the in-group: white boys. Being a black boy put me in the out-group.

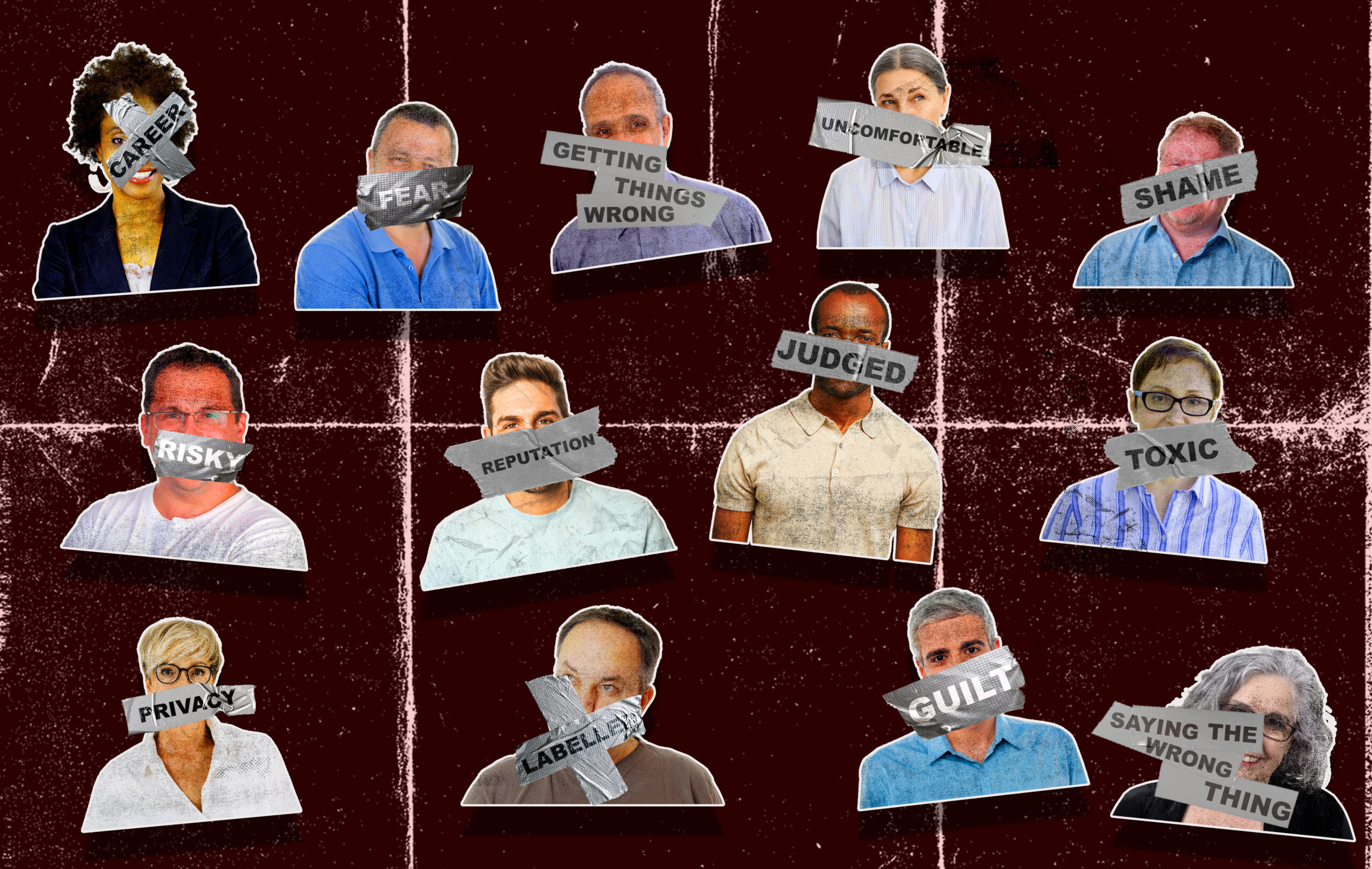

Without early intervention, these social hierarchies become normalised and accepted as natural. Some people have less because they are less; some have more because they are ‘better than’ and so deserve more. Deprived of good quality conversations about our differences and sameness, children internalise prejudice and can unwittingly work against both their own and others’ interest.

From there are sown the seeds that undermine our social fabric – now and in the future – and jeopardise our very survival.

How in-group bias plays out in social activism

Racism is a distortion of human relationships, created by in-group bias and inequitable distribution of power. It poses an existential threat by creating competing priorities just when we need to work collectively.

As an illustration, social activism on the political left, where people share liberal values of equity and inclusion, is never completely free of racial bias or inequality. It’s an issue I’ve highlighted in previous articles and podcasts.

It’s not incidental that an issue like climate change receives more investment, media coverage and political and public engagement than racial inequity. There’s been more progress on this in a decade than on racial equity in the last half century. It’s because the white middle class (from the left and right) prioritises climate change and has the power to drive this agenda forward at pace.

Those of us who agree that both a net-zero economy and racial equity are important will divide, broadly speaking, along racial and socio-economic lines when pushed on which we should prioritise.

For example, many of the poorest – a disproportionate number of whom are black – would prefer to have their basic needs met before investing in upgrades on inefficient heating systems or polluting cars. This has been Rishi Sunak’s recent argument for delaying emission reduction targets.

We are less able to deal effectively with an existential threat like climate change if we are divided. So we must treat the division itself as a primary threat. The more equitable a society and a world we become, the more robust we will be in dealing with crises that demand collective action.

So black people’s voices are needed in the climate change debate. Our perspective adds something new to the argument, based on our own biases. Bias is not wrong; but a diversity of biases (or perspectives) creates greater equity which makes us stronger.

What does this mean for me as an activist?

Activism at its best seeks the sharing of different perspectives, new knowledge and a more equitable distribution of power. Any quashing of a person’s ability to be active is a burn to the individual and to society. In this sense good activism, even when it disrupts, is very much pro-social rather than anti-social.

Coming back to my antipathy to activism as a child: I experienced discrimination living in a society where in-group bias, combined with unfair distribution of knowledge and power, distorted my thinking. The natural tendency for me to have a bias towards the black community was subverted. I preferred white people, so much so that I silenced myself to win approval and was ashamed of those in my community who did the natural thing – using their voices to ask for what was rightfully ours.

Having found activism through writing, I use it to disrupt the status quo to create greater unity. Being an activist isn’t an act of separation from society, it’s a statement of belonging. The more I write the greater my sense of being part of – rather than separate from – society.

Activism has connected me to who I am, and to who we are. We are black, but we are the same. We are women, but we are the same. We have a disability, but we are the same. We are refugees, or economically-deprived or gay, but we are still the same. We demand equity as human beings, and it is nothing to be ashamed of. It is necessary for our very survival.

My uncomfortable stance on climate change

If I had to put it into words, what drives my activism is the racially equitable distribution of money/wealth by any legal means necessary. This often involves holding seemingly competing ideologies, and I regularly find myself on what feels like the ‘wrong’ side of the political argument. Good long-term policies can have unintended short-term consequences and too many of these disproportionately affect Black and Brown communities.

Take Rishi Sunak’s recent U-turn on a range of policies designed to achieve the UK’s net zero targets. He has ditched some and delayed others by 5 years to 2035. Given the inequitable distribution of wealth in the UK, I instinctively support this policy shift because of its immediate benefit to Black communities. Unlike many of his critics, I’m less concerned with his possible motivations than with the practical outcomes; especially for those who can least afford the initial costs of reducing their carbon emissions – who are disproportionately from Black and Brown communities.

An equitable transition demands that those who have most pay most. An effective transition means that we remove polluting vehicles from the system altogether, and not export pollution to other parts of the UK or the world, by reselling old cars on the open market. To have both an effective and equitable solution we need to fully subsidise the cost of transitioning for those who can least afford it. Current efforts to do this are underfunded and simply leave too many people behind. For example, while the wealthiest move to low emission cars and continue to drive in London, those least able to replace their old cars are faced with daily charges of up to £12.50 per day. Their only other option is to absorb an up to a £3k loss if they apply to the Mayor of London’s scrappage scheme; which provides a grant subsidy (typically less than the value of the car) when someone chooses to get rid of a polluting car. For those without cars – again, disproportionately Black and Brown communities – there are few benefits without better or free public transport.

I’m torn by my position on this because on the one hand I am allied with a policy that is short term and politically expedient, but on the other, from a race equity lens, one that feels more realistic and fairer. I’ve heard the arguments about the longer-term negative implications of this policy change, including on the least wealthy; but long-term thinking is a privilege. Financial survival means that those who have least don’t have the luxury of thinking beyond the next pay cheque; spending thousands to reduce their carbon emissions is a social necessity too many just can’t afford.

In terms of transitioning to net zero, wealth divides us into those who can and do, those who can but don’t, and those who simply can’t. For this last invisible group, the imposition of inequitable net zero transition policies is (at the very least) a significant inconvenience and at worst a financial tipping point into destitution.

The ideal would be to stick to the original net zero targets and properly subsidise the investment in transition for those who can least afford it. Beyond the initial transition costs there would need to be an investment in new technology to make sure that any ongoing costs associated with running and maintaining any new eco-tech (e.g. an electric car or a heat pump) are kept as low as possible.

Effectively we would need to invest in accelerating the eco tech revolution and protect the poorest whilst this is happening. We are not yet there.

Whatever Rishi Sunak’s reasons for the change to net zero targets, the principle of ‘taking the poor with us’ in the transition to net zero is the right one. Even if that principle is maintained for disingenuous reasons, I’ll support it, whatever side of the political fence it leaves me on. For the poorest the practical outcome of financial survival is more important than the political manoeuvres that deliver those outcomes. Those debates and any subsequent participation in the political process are, unsurprisingly, left to those who have the money and time to engage.

This brings me back to what drives my activism; a more equitable distribution of wealth leads to greater participation in political discourse and in the political process; and political engagement makes for a fairer, more cohesive, and more democratic society, which benefits us all.