Whose “lived experience” matters most? (article)

There is a new belief that any debate about racial inequality – its causes, impacts and solution – should be driven by those with ‘lived experience’. Increasingly, funders are embedding this thinking into policy, making participation of people with ‘lived experience’ part of their funding criteria. And white leaders are using it to excuse themselves from race conversations – or at least to be less vocal.

The intention is good; to increase the impact of social justice programmes and to empower those affected by giving them a say in the programme design and implementation. But it raises serious questions about the benefits of relying on lived experience in dealing with racial inequalities.

How do we decide which lived experiences matter most, given the ever-increasing fragmentation of identities and perspectives on solutions to racial inequity? And within current power structures, can white people ever be excluded from driving solutions on racial inequality?

Activists versus Assimilationists

According to YouGov research, 84% of people from black communities say they have experienced racism to some extent and agree action needs to be taken to eradicate it. However, this belies the fact that although we share lived experiences of racism, we each process and cope with them differently. As a result, views vary widely on strategies for addressing the problem.

Within my friendship group alone, opinions range from those who believe that racism is best challenged through social and political action (Activists), to those who think our energy is better spent ‘fitting in’ and becoming successful (Assimilationists).

These strategies vary not only between socially defined racial categories but also within these categories (e.g. Black, East Asian, South Asian etc). And of course, different people balance these strategies in individual ways. Given the range of possible responses, how do we actually decide who to listen to when implementing solutions.

Usually, the lived experience of the most vocal takes priority over those who are politically quieter. Activists shout louder than Assimilationists and hold sway when influencing the language used in communications (political correctness), publicly stated positions (PR) and policy on racial inequity. But rarely does this convert to real change in practice.

The money does not follow the strategy

Taking the arts sector – and the Arts Council in particular as illustration – all its major policy communications talk about creating a more inclusive sector with a greater diversity of arts output. But if we follow the money, it’s clear their policy on grants distribution is neither inclusive nor diverse.

Only 2.4% of ACE funding goes to Black-led institutions – this should be 14% if distributed in proportion to the BAME population. Compare that to 14% of ACE funding which goes to opera alone. Funding is heavily skewed to the major arts institutions and to assimilating (some would say encouraging) Black communities into accessing niche art forms produced and curated by white people.

Given the weight of investment committed to the major institutions, ACE’s diversity strategy – and budget – have been directed at diversifying the boards, staff and content of the existing major opera houses, theatres and museums. It has not attempted to redistribute funding equitably to create a wider diversity of institutions and art forms.

No matter how strong the voices are, no matter how much we bring lived experience to the centre of the decision-making process, these views are inevitably mediated by those in power, who are predominantly white.

White leaders must not exclude themselves

This is what drives the struggle between the disparate parts of the Black communities to be heard. There is no monolithic lived experience. Yes, there are common lived experiences, but when seeking solutions to the problems we face, there are too many views and perspectives to be heard.

Ultimately someone decides on which lived experiences to privilege. To exclude white voices from the conversation makes no sense, and is not possible given current power structures. So it is important that white leaders do not exclude themselves, shielding behind the politically correct notion of empowering those with lived experience.

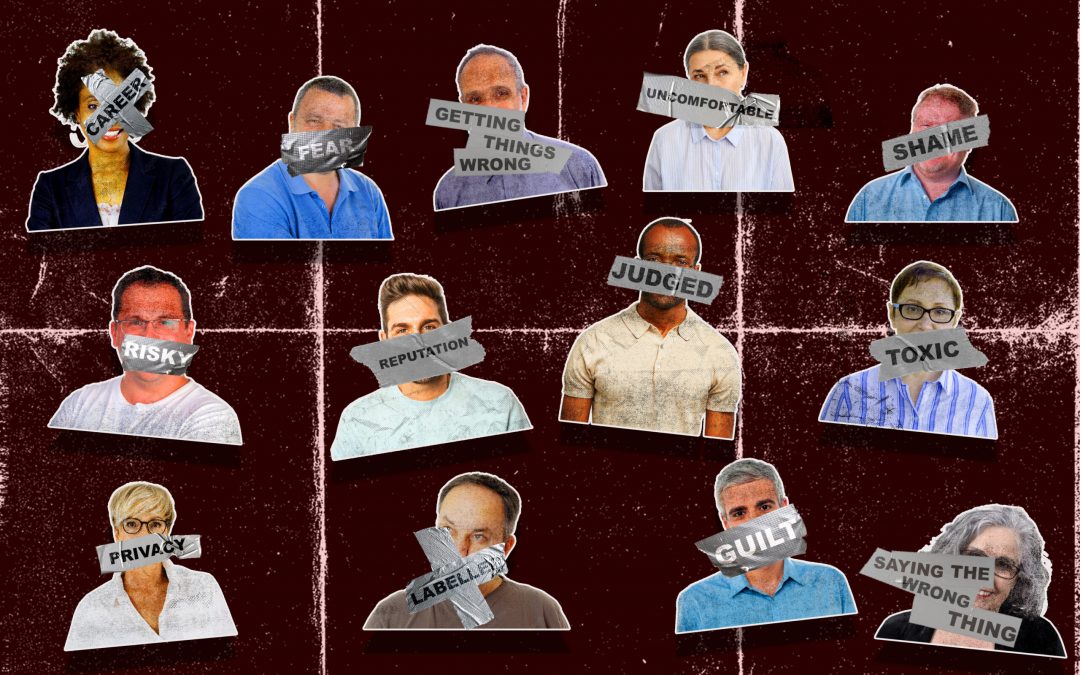

You are the power brokers and it’s important to be transparent; to acknowledge that in your decision making some voices get heard while others are silenced. The work, therefore, lies in more equitable funding which would enable a wider range of interventions from a more diverse range of lived experiences.

The money is there. Your work is not to remove yourself from the conversation but to distribute it equitably.

We are keen to keep the conversation going. To read more and share your thoughts on this or other articles, connect with me on LinkedIn.

NB. We have used the term Black. We recognise the diversity of individual identities and lived experiences, and understand that Black is an imperfect term that does not fully capture the racial, cultural and ethnic identities of people that experience structural and systematic inequality.

NB. Although we agree that equitable funding is important for all groups, we are talking specifically about racially equitable funding at this time.